3D printing could shake up construction industry and bring tech to the moon

A young CEO who started a 3D-printing business to create what he believes are faster, cheaper, more hurricane-resistant and environmentally-friendly homes, is also working with NASA to pioneer 3D printing on the moon.

By the end of the decade, a printer from Jason Ballard's company, Icon is scheduled to fly to the moon to test print part of a landing pad as part of a partnership with NASA. Closer to home, Icon hopes its 3D-printing technology can eventually help address a serious housing deficit in the U.S.

Why Jason Ballard views 3D-printed homes as the future

The U.S. is short about 3.8 million housing units, both for rent and for sale, according to the most recent estimates from Freddie Mac. What is available is out of financial reach for most Americans. An analysis of homes that went on sale last year, done by the real estate website Redfin, revealed that only 21% of them were affordable for the typical buyer.

Ballard's initial career plan had been to become an Episcopal priest.

"But along the way, I started just, getting this, like, itch about housing not being right," he said. "So I studied conservation biology. I got involved in sustainable building, and I worked at the local homeless shelter. And so now I'm thinking about homelessness and I'm working in sustainable building. Along the way, my hometown gets destroyed by a hurricane."

When he was approved to go to seminary, he sought guidance from the Episcopal bishop of Texas, who, he says, told him, "Jason, I want you to pursue this housing thing like this is your priesthood; this is your vocation."

Ballard co-founded Icon in 2017 with Evan Loomis, a college friend with a background in finance, and Alex Le Roux, a Baylor engineering graduate. Their first small 3D printed home, which was unveiled at the SXSW festival in 2018, landed them a meeting with Alan Graham, the founder of a first-of-its-kind village called Community First! Village, which provides small homes to several hundred formerly homeless men and women.

Icon 3D printed a welcome center and six small houses at Community First! Village. That's how Tim Shea, a 73-year-old man who'd battled heroin addiction for decades, in 2020 became the first person in this country to live in a 3D-printed home.

"I would resign if I was only allowed to build luxury homes, and we would go bankrupt right now if all we built was 3% margin homes for homeless people," Ballard said. "But once this technology arrives in its full force, I think it fundamentally transforms the way we build."

It's not just about cost

Ballard views 3D printing as a needed paradigm shift in the construction industry. He argues that traditional stick frame housing is susceptible to hurricanes, fires, and termites. To cut costs, Ballard says developers often trim quality on materials and labor, and they create cookie cutter developments.

"We are not succeeding at something we have to get right. And on top of that, it's an ecological disaster," Ballard said. "And I would certainly say, and I think you would agree, it is existentially urgent that we shelter ourselves without ruining the planet we have to live on."

As Ballard explains it, conventionally built walls involve multiple steps and building materials: siding, moisture barrier, sheathing, studs, drywall, float, tape and texture. Conversely, 3D-printed walls are built with a single material, which is delivered by a robot. Ballard also argues that 3D printing generates less waste.

How 3D printing homes works

Icon's process starts with one-and-a-half-ton sacks of dry concrete powder, which get mixed with water, sand and additives. The mixture is then pumped to a robotic printer.

The printer follows a pre-programmed floor plan, with a nozzle that squeezes out the wet, concrete mixture layer by layer. Each layer is called a "bead" and takes about 30 minutes to lay down, Conner Jenkins, Icon's senior construction project manager, said. By the time one complete pass is done, the layer has hardened enough to support the next bead. Steel is added every 10th layer for strength, and cutouts are left for plumbing and electricity.

It takes about two weeks to print a full, 160-bead house.

For now, Icon is only 3D printing the walls of its houses. Roofs, windows, doors and insulation are added the old-fashioned way.

The technique is being used to build what will soon be the world's first large community of 3D-printed homes. Icon is printing 100 houses as part of a huge, new development north of Austin, Texas called Wolf Ranch. The 3D-printed homes will start in the high $400,000 range.

NASA's partnership with Icon to bring 3D printing to the moon

Ballard, who once applied to be an astronaut but was rejected, is thinking beyond firsts on Earth. Icon has partnered with NASA to pioneer 3D printing on the moon.

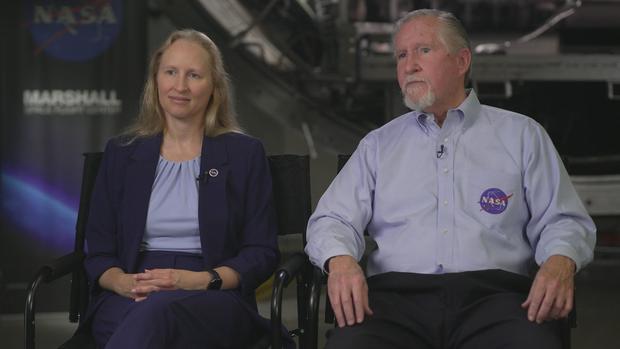

NASA has announced a series of Artemis missions with the goal of returning American astronauts to the moon for the first time in more than 50 years, this time to stay. Staying on the moon requires infrastructure, including landing pads, roads and housing, which can't easily be transported from the Earth. At Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, NASA scientists Jennifer Edmunson and Corky Clinton run a program called MMPACT, Moon to Mars Planetary Autonomous Construction Technologies.

"We want to be able to make structures that we need without having to be tended by astronauts," Clinton said.

Clinton and his team at NASA had long been interested in 3D printing as a potential technology for building on the moon, so when he heard about Icon's early 3D printing work, he traveled to Austin to inspect it. NASA gave Icon development money in 2020 and then, last fall, a $57 million contract.

Ballard and Evan Jensen, who's leading the project for Icon, are working to figure out the fundamental challenge: how to 3D print infrastructure on the moon without having to ship material there from Earth. It means using what's called lunar regolith, which covers the moon's surface, rather than concrete and water, as a building material.

"Regolith is made up of rock that has been pummeled over billions of years from asteroids, comets and things," Edmunson, the NASA scientist, said.

Icon has a big tub full of simulated moon regolith in its Austin facility, and has invented and built a robotic system to 3D print with it. The company has created a new way to 3D print -- using lasers. Instead of a nozzle squirting out soft concrete, a high-intensity laser beam melts the powdery simulated regolith to transform it into a hard, strong, building material. They're running experiments now, using the laser to create a small sample.

Icon sends their test prints to NASA, where they're blasted with a plasma torch that reaches almost 4,000 degrees, to see if the materials can take the heat a landing pad would have to withstand. The next test will be operating the robotic arm and laser inside NASA's thermal vacuum chamber, which mimics the moon's extreme cold, heat and vacuum conditions.

"We can see the steps and the technology to get us there," Edmunson said.

Ballard and NASA aren't stopping at the moon - they view 3D printing on Mars as a realistic future ambition.

While working on the NASA project, Icon continues to formulate new mixes to reduce the carbon footprint of its concrete for buildings on Earth. The company is also trying out more radical architecture, including advanced geometric designs, domes, and patterned walls. Next year, Icon will print round hotel rooms in Marfa, Texas and futuristic-looking designer homes.

Are Ballard's plans too good to be true?

Ballard is aware of the skepticism surrounding CEO's of young companies overpromising and hyping, and he says he sometimes hesitates to even share what he sees coming in the future. When pushed, though, he says, "In the future, I think most buildings will be designed by AI; most projects will be run by software; and almost everything will be built by robots. And I don't think that's that far away."

What's more, he says, "Housing will be more abundant, more affordable, [and] more beautiful."

When asked whether these predictions might fall under the category of 'too good to be true,' he says, "But cars and airplanes and the moon landing seemed too good to be true for a moment as well. And so, like, maybe the only proof I can give you is, like, I'm betting my life on it. Like, I have this one precious life to live, and I'm using it to do this."

Reported by Lesley Stahl, Shari Finkelstein, Collette Richards.

for more features.